Earning the Green Beret

Becoming a National Guard Special Forces team member

Story by Sgt. 1st Class Chad Menegay, Ohio National Guard Public Affairs

COLUMBUS, Ohio (12/22/20)

By most composite measures, the U.S. Army owns a reputation — worldwide and historically — as the best, most powerful, strategically responsive, highly-trained and technologically advanced of armies. There are some who join or stay in the Army because they are drawn to be among the best. Motivations to serve, of course, run the gamut, and there is perhaps no clear primary motivation to serve over another. Still, it is generally accepted that while one is part of the U.S. military, one is among the best. For one to be among the best of the best, however, that is another set of measures altogether, and many will look to Special Forces as an ultimate demarcation. They might also do well to look to the Army National Guard.

Among the 336,000 Army National Guard members who make up about a third of the entire U.S. Army, there are somewhere over 1,000 Special Forces team members, so nearly 1 in 300 Army National Guard members are Special Forces. It’s an exclusive group with a demanding pathway to earn the Green Beret, but the opportunity is there for those with enough ambition and heart.

Two Ohio Army National Guard Soldiers passed Special Forces Assessment and Selection (SFAS) earlier this year, qualifying them to attend the 53-week Special Forces Qualification Course (SFQC): First Lt. Seth Kilian, an engineer officer assigned to B Company, 2nd Battalion, 19th Special Forces Group in Columbus; and Sgt. Elliot Timmons, a combat medic with Company C, 237th Support Battalion in Akron, Ohio. Kilian’s goal is to become a Special Forces officer after the qualification course, and while Timmons is pursuing qualification as a Special Forces medical sergeant.

The two spent about six months with 19th Special Forces Preparatory Detachment (SFPD) conducting physically demanding training including running, ruck marching, pushups, situps and land navigation as part of thier assessment and then endured the strenuous 21-day SFAS course.

“We meet at Fort Bragg, (North Carolina, home to U.S. Special Operations Command headquarters) and they take us to Camp Mackall (a sub-installation of Fort Bragg and primary training facility for Special Forces candidates),” Timmons said. “No cell phones. They take that when you get on the bus. You show up, download your gear, and you just start receiving orders. Day zero, you’re ready to go. You’ve got to run everywhere, which is a pain. There’s a lot of loose gravel.”

National Guard Special Forces candidates run to the point of physical exhaustion alongside regular Army candidates through a gauntlet of cadre-devised difficulties and discomforts.

“Grueling,” Kilian said. “It’s pretty terrible on your body. I’ve never seen so many men in so much pain, but it was a lot of fun. Everyone has ‘A’ personalities, and everyone is on top of one another, but it’s a good challenge to be able to work as a team and use your individual skill sets. You’re there with guys who have a bunch of different military occupational specialties. A lot of active-duty people come from an infantry background, but, especially the Guardsmen, we had the engineer background, truck drivers, electricians, carpenters, just anyone can go. So, I’m mechanically minded and was able to do a lot of the knot tying and build things and make things, so I was more of like a worker bee, and you need those people to be successful. You need people to be able to both follow, but also lead at times, and going through ‘the suck’ together brings you closer.”

Candidates are tested mentally and physically as individuals and teams. Cadre are often watching and taking mental notes, looking for the self-motivated Soldiers, as candidates practice their survival skills and run through a myriad of mental tasks designed to test their capacity for working through frustration and the ambiguity of not always having full information in their attempts to solve problems.

“You need grit to succeed in Special Forces training,” Kilian said. “There was one guy at selection who finished the long ruck and full course with a fractured ankle. That right there shows the mentality of what is necessary to go through and push and just keep going because there’s no stopping. It’s a do or die thing.”

As an officer, Kilian, who works as a furniture designer in the civilian world with an industrial and innovative design degree from Cedarville University, will need to become airborne- and Ranger-qualified prior to attending SFQC and then also complete a secondary language course.

“I’m motivated to do my best in this Army career, so I thought ‘the best would be the Green Berets,' so there’s been a lot of setbacks, hurdles and pain, but definitely the doors have been opening, and as long as they do, I’m going to continue to pursue down this path,” Killian said.

Kilian, who always keeps a Bible in a shoulder pocket of his uniform, began developing his never-quit mental state as a leader at Canaan Christian Academy in Lake Ariel, Pennsylvania, as the captain of the school soccer team, he said.

“I liked to challenge myself and others, pushing physically and mentally,” Kilian said. “I thought of myself as a servant leader, and that’s something I return to in my mind to this day. I like to encourage others.”

Kilian, who is always looking for ways to credit others for his own success, also said he found personal encouragement from training with America’s most elite Soldiers and in working one-on-one with cadre.

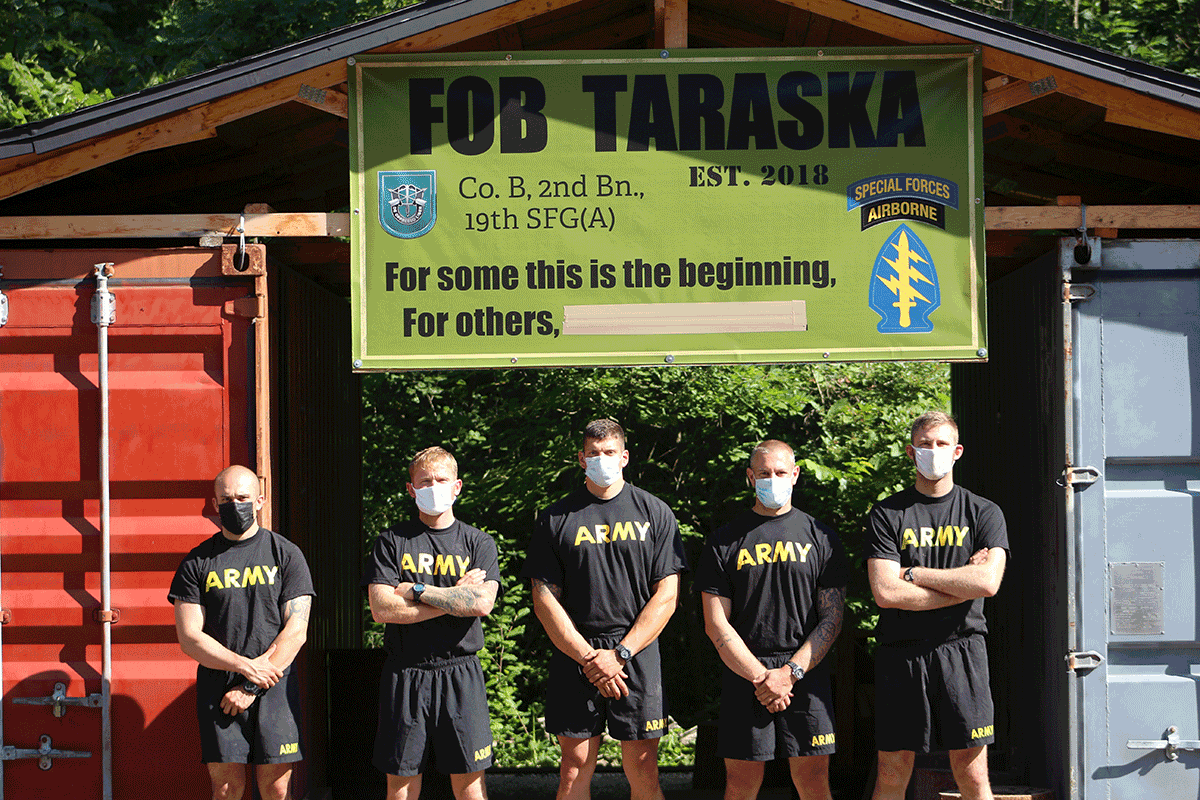

SFPD cadre who assess candidates are looking for humble individuals who care about the mission and have no concern for awards, said Sgt. 1st Class Philip A. Taraska, the Ohio Special Forces 19th Group SFPD noncommissioned officer in charge.

In preparing individuals for selection, Taraska said “we want you lean, trim, cut and ready to roll. You need to have more of a triathlete mentality instead of bulking up and being a crazy weightlifter, so a lot of guys will change their training routines.”

Of course, serious physical preparation is necessary, but Timmons said, for him, mental preparation was equally if not more important for success.

“To mentally prepare for Special Forces, whether it be a training weekend or selections, I really put the worst possible scenario through my head,” Timmons said. “I’ll think ‘alright, day one I’ve already got bad blisters that are already bleeding. It’s not going to stop. It’s storming, but the mission still has to go on,’ and I’ll think ‘you’re not going to quit.’”

Timmons was in paramedic school at Cincinnati State when he took a few weeks off to attend selection, but then graduated from Cincinnati State and went on to Army Basic Leadership Course and the three-week Airborne School. Schooling has been his job lately. Timmons will now attend an 18-month qualification course that is argued to be equivalent to the training a medical doctor would receive with residencies in trauma medicine and emergency rooms, and he’ll get to learn French too.

“To accomplish this much, so far, is great,” Timmons said. “But I’m going to stay humble. I want to get the beret, and I’m going to do everything within my power to achieve that goal.”

Timmons said he has pursued Special Forces because he wanted to work with the best and wanted to improve himself physically and mentally via the military.

“There’s a lot of time sacrificed, a lot of studying,” Timmons said. “Leaving friends, family behind, missing out on birthdays and weddings. It takes a lot of determination and discipline.”

After qualification, Timmons said he will essentially be a physician’s assistant, but he plans to go back to college to earn the degree. He is a lifelong learner with a growth mindset, and said that comes from his family’s influence since he was a child.

“One phrase that I always think of is, from my grandfather, (a Marine who fought on Iwo Jima during World War II and taught history) who passed away in 2015: ‘If you set your mind to it, you can accomplish anything,’” Timmons said.

Timmons and Kilian could one day find themselves accomplishing unimaginable things in Africa, Europe or Southwest Asia, speaking a secondary language with foreign leaders, advising, assisting, teaching and perhaps making mission-critical decisions that impact whole regions and ultimately the U.S. itself.

“We’re still getting out with all our counterparts and living with them across the world,” Taraska said. “That’s the bread and butter of Green Berets — unconventional warfare — working with our counterparts, living with them, getting to know them, knowing the language and being humble Soldiers at the end of the day, understanding that we’re going to accomplish a lot, and it’s not going to make the news, and that’s cool. We’re fine with that.”