‘…Manila Would Do’: Marking the 75th anniversary of the Battle of Manila

Story by Sgt. 1st Class Joshua Mann, Ohio Army National Guard Historian

(03/03/20)

In March 1942, Gen. Douglas MacArthur made his famous “I shall return” speech just after making his escape from the Japanese in the Philippines. After three long years of island hopping, MacArthur returned when the Sixth Army landed at Lingayen Gulf on Jan. 9, 1945.

But just returning to the Philippines was not enough for MacArthur. His ultimate goal was ripping the capital city of Manila from the horrors of three years of Japanese control. The spearhead of this mission was Ohio’s 37th Infantry Division, now veterans of four years of active service and two bloody jungle campaigns: New Georgia and Bougainville.

After landing at Lingayen, the Soldiers of the 37th worked their way down the central plains of Luzon against sporadic enemy defenses. On Jan. 27, the 37th swung a portion of its force west to attack the Fort Stotsenberg/Clark Field area. At the same time, the 148th Infantry continued the “race for Manila” with the mechanized 1st Cavalry Division.

“Ringing in my ears, however, were the words of Gen. MacArthur who had visited me on at least three occasions as I headed down the road. Each time when he departed, he said “White, go to Manila; go to Manila!” wrote 148th commander Col. Lawrence White in his 1999 memoirs.

After marching 150 miles in less than a month, the 3rd Battalion, 148th Infantry entered the northern suburbs of Manila by daylight of Feb. 4. “We got one 10-mile ride and we hoofed it in the rest of the way,” declared 148th veteran Rayford Anderson in a 2004 interview.

Late in the day of Feb. 4, Anderson and a squad of men from Company F, 148th Infantry pried back a board at the old Bilibid Prison to discover 465 civilian internees and 810 American prisoners of war from the first Luzon Campaign.

The following day, Feb. 5, the Japanese began to set fire to a district of Manila known as Chinatown. Caught in the roaring inferno was Company K, 148th Infantry. 2nd Lt. Robert Viale’s 1st platoon was leading the company’s withdrawal from the blaze, when it ran into a Japanese machine gun that blocked the only escape route. Viale led a group of men to a building adjacent to the position and attempted to throw grenades down onto the gun from a second story window. When one of the grenades slipped from his hands, Viale grabbed it and using his body to protect his Soldiers, absorbed the exploding grenade and died a few moments later. His actions would lead to the awarding of the Medal of Honor.

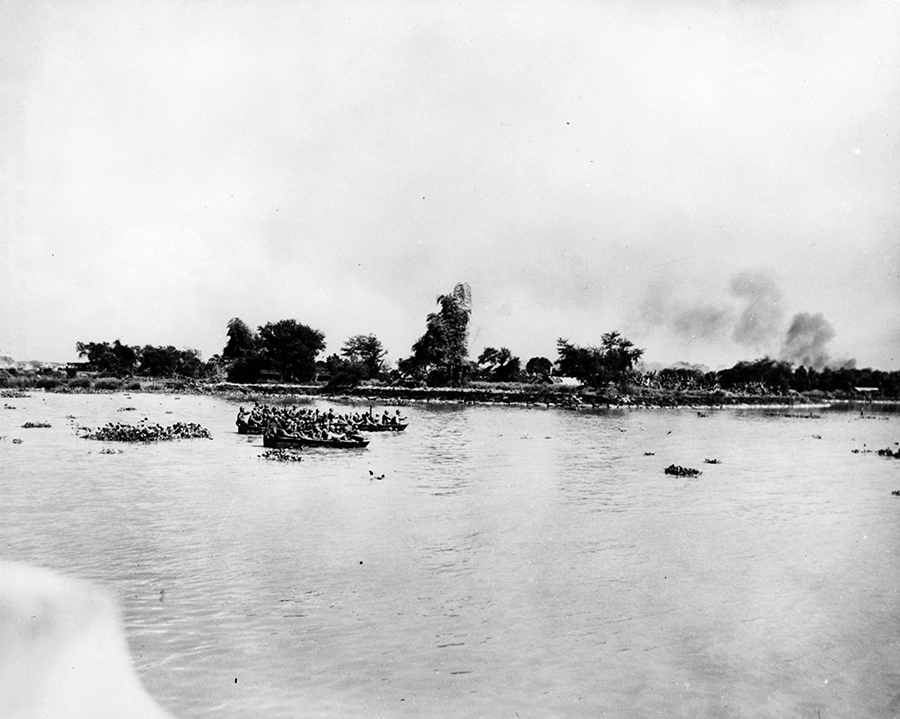

On Feb. 7, the 37th relieved the 1st Cavalry Division at the Malacanan Palace along the Pasig River, and in a few hours made an amphibious crossing in plywood assault boats to the south side of the river. American troops, led by the 37th, were now pouring into Manila south of the Pasig.

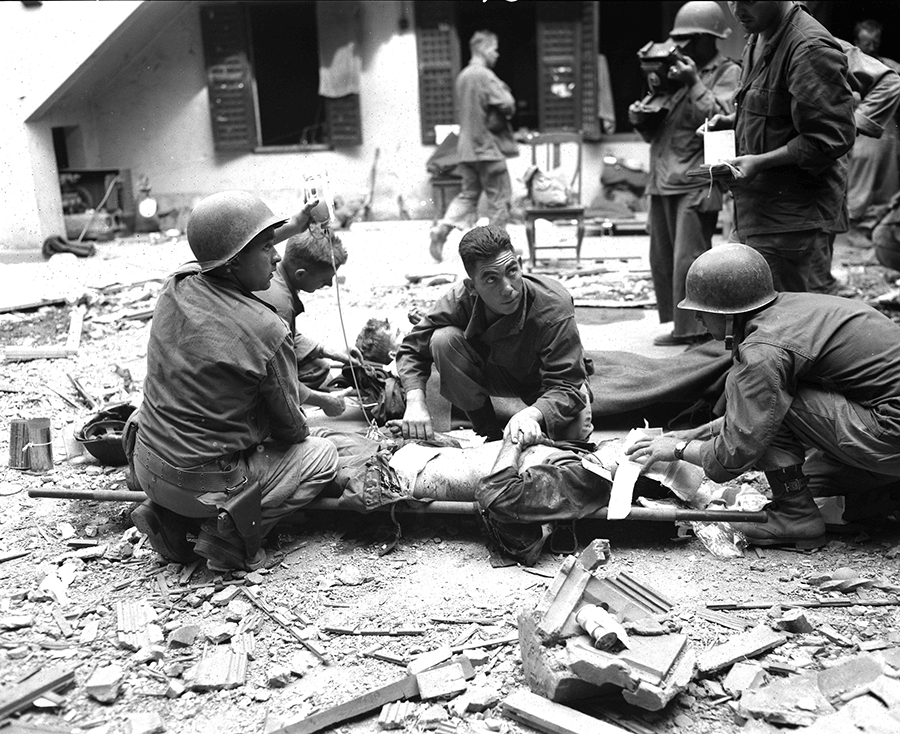

Fighting through the Paco District on Feb. 9, three more members of the 148th Infantry earned the Medal of Honor for their heroic deeds. At the Manila Gas Works, Pvt. Joseph Cicchetti, of Company A, assembled a litter team that rescued 14 men in four hours before he was hit by a shell fragment while carrying a wounded Soldier to safety. At the heavily fortified Paco Railroad Station, two Browning Automatic Riflemen of Company B — Pvt. Cleto Rodriguez and Pfc. John Reese Jr. — left their platoon to advance under fire and engage the enemy for over two hours. The team killed 82 enemy and completely disorganized their defense. On their return to their platoon, Reese was killed. Of the seven Medal of Honor recipients in the 37th during World War II, Rodriguez was the only living recipient.

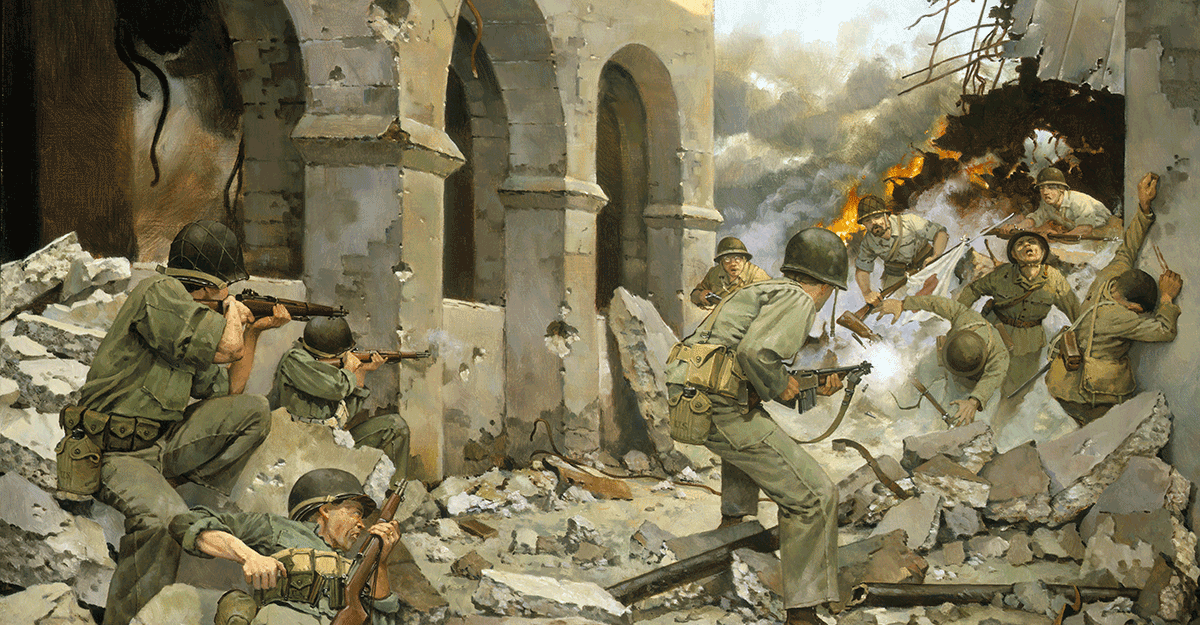

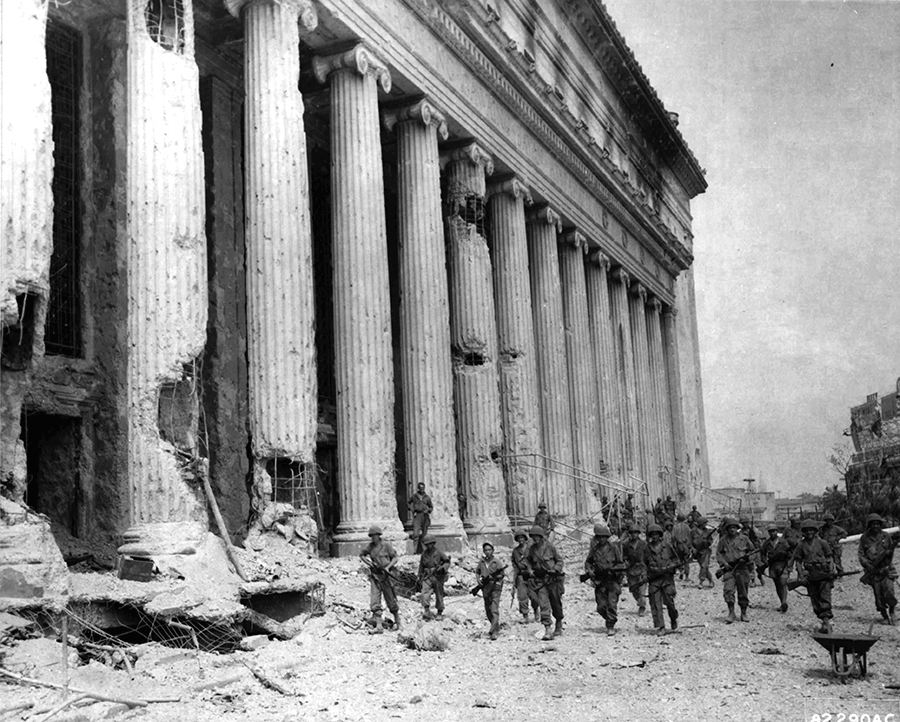

As the Americans squeezed the enemy into a final pocket, die-hard Japanese soldiers turned every building into fortified strongpoints. The General Post Office, YMCA, city hall, Philippine General Hospital and University of the Philippines campus were just a few of the seemingly impregnable fortresses that fell to the 37th. Buckeye artillery, mortars, tanks and tank destroyers began to pulverize enemy positions before doughboys attacked. As infantrymen moved through and mopped up these areas, it was soon discovered that the Japanese defenders had turned to murdering thousands of innocent Filipino civilians, including women and children.

“The atrocities committed against innocent Filipino civilians have filled us with hatred,” wrote Maj. Gen. Robert S. Beightler, the 37th commander, following the battle. “The sheer bestiality of which they were capable is beyond our comprehension.”

By Feb. 23, the Buckeyes had cleared enough of the strongpoints to make an assault on the famous walled city of Intramurous, a 16th century Spanish fort. Prior to the 145th and 129th Infantry attacking, point blank artillery fire plastered Intramurous until, as Beightler described, “it was a mess. It fell to us with ease we never expected.”

The final series of government buildings —finance, agriculture and legislative — met the same fate and were secured in the final days of February. After 27 continuous days of ferocious city fighting, Manila was declared secure at 10:45 a.m. on March 3. It is estimated that the 37th killed over 13,000 enemy in Manila. The battle cost the Buckeyes 3,813 casualties, including 411 dead. The Battle of Manila remains the only urban battle fought in the Pacific during World War II.

“For those who missed Normandy or Cassino, Manila would do,” reveals the 37th Infantry Division history.

Three units of the division would receive the Presidential Unit Citation for Manila, the 148th Infantry, 117th Engineer Battalion and the 637th Tank Destroyer Battalion. In addition to the four Medals of Honor, hundreds of other awards for valor were presented to 37th Infantry Division Soldiers.

“The instances of heroism that came from the fighting there have become legion,” described Beightler in his address to Ohio legislators after returning from the Pacific. “Day and night, week after week, fighting, dying, snatching a wink of sleep in a rubble heap with bullets splattering the walls around, dashing into almost certain death with never a semblance of faltering — such was the life of the doughboy fighting in Manila.”