Ohio Army National Guard Historical Collections

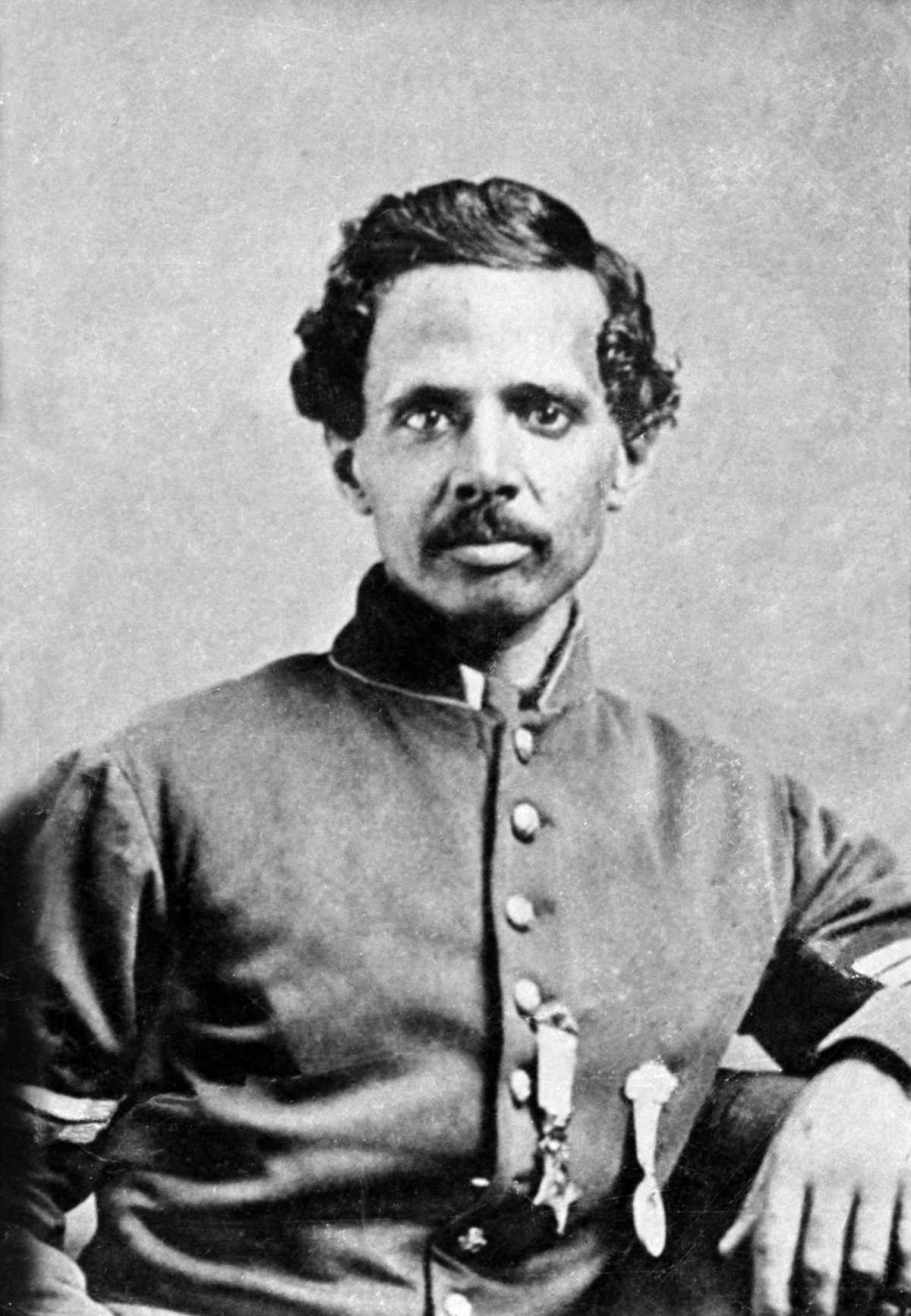

Powhatan Beaty, born a slave in Virginia, later moved to Cincinnati and became free. He entered service in the Civil War as a member of the Ohio Volunteer Militia, the predecessor to today’s Ohio National Guard, and later joined the Union Army, earning the Medal of Honor for his heroics at the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm in September 1864.

Ohio Medal of Honor recipient: From slavery to freedom

Story by Staff Sgt. Chad Menegay, Ohio National Guard Public Affairs

A 24-year-old farmer from Greater Cincinnati enlisted into the Ohio Volunteer Militia, a precursor to the Ohio National Guard, on June 7, 1863, presumably, to fight the Confederacy under the banner of freedom.

For Powhatan Beaty, who grew up a slave in Richmond, Virginia, what would that fight for freedom mean, given that over 4 million of his fellow black Americans were still enslaved?

It likely meant an end to 200 whiplashes in a day, the branding, the rattle of shackles and chains, the severance from family sold, the sexual assault of loved ones, the friends hanged or burned alive or shot by firing squad, the mutilations or the solitary confinement in a hot box.

For Powhatan Beaty, who stood 5 feet 7 inches tall and had a promising career as an actor and playwright ahead of him, what would that fight for freedom mean for his immediate future, given that over 620,000 men died and many more were wounded, some maimed for life, in the Civil War?

It likely meant carnage and maybe worse: the ground-shaking artillery barrages, the shattered bodies, the wound infections, the bone-sawing amputations, the nightmares of shell shock, the chills of yellow fever, the smallpox lesions, the dehydration and the malnutrition.

Still, Beaty was both ready and there for his country, willing to answer the call in the face of war and its probable horrors.

“Soldiers like Beaty fought to end slavery; that was their prime motivation,” said Anthony Gibbs, with the Ohio History Connection. “The second thing they were fighting for was citizenship. Even though they lived in a free state at that time, they still weren’t allowed to vote in many places. They still were not allowed to take public office. They couldn’t send their students to public schools and such. They believed that by fighting for President Lincoln and the Union that they could gain basic and full citizenship rights. The third thing is that they wanted to disprove this theory that they were somehow unequal because of their race, that they were somehow inferior.”

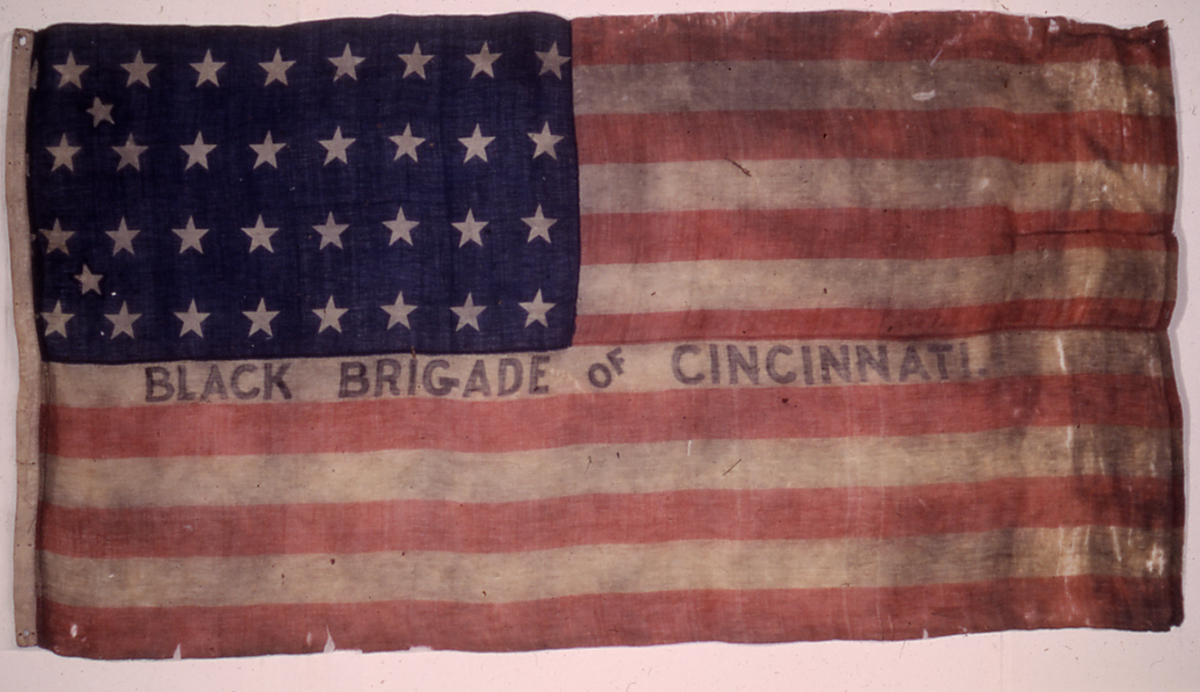

The Black Brigade

Beaty’s service began in defense of Cincinnati, then the sixth-largest city in the U.S., from Confederate forces as part of the Black Brigade.

Cincinnati Mayor George Hatch ordered the police department to round up all able-bodied black males for work on the Northern Kentucky fortifications. Men were forced from their businesses and homes by bayonet and gunpoint on Sept. 2, 1862, to a mule pen on Plum Street in downtown Cincinnati.

“They didn’t ask,” Gibbs said. “There definitely were good people who would have volunteered, and there were those who did volunteer, but it was in the middle of the night when they just ran up and opened the door and forced all the men to come out, which makes this story a little more negative than it should be because you had men who were willing and ready to serve and help protect their city, to protect their government, to protect their families, but they were forced out of their homes and gathered all together in a very negative way.”

For the next 15 days, Beaty dug rifle pits and trenches, cleared forests, and constructed roads and forts.

Union Gen. Lew Wallace said, “When the history of Cincinnati during the past two weeks comes to be written up, it will be said that it was the spades (a then-popular derogatory term for black people) and not the guns that saved the city from attack by the Rebels.”

Battle of Chaffin’s Farm

Beaty then joined the Union Army as a private but was promoted to sergeant just two days later; he took charge of a squad of 47 other recruits.

“These Soldiers were living in a time where there’s a general feeling that your race made you inferior, and they had to fight against that,” Gibbs said.

It took years for blacks to be allowed to join the battle for the Union, but eventually they were afforded the opportunity, and, by the war’s end, blacks made up 10 percent of the Union’s fighting forces.

For Ohio, blacks were first given a chance to fight when Ohio Gov. David Tod asked the U.S. Department of War to form an African-American Ohio regiment. Permission was granted, and on June 17, 1863, Beaty and his squad became the first Soldiers of the 127th Ohio Volunteer Infantry in Delaware, Ohio, which was later reorganized as the 5th United States Colored Troops (USCT).

By the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm in Virginia on Sept. 29, 1864, Beaty had climbed to the rank of first sergeant in Company G. His regiment was part of a division of black Soldiers assigned to attack the heart of Confederate defenses at New Market Heights.

The attack was met with extraordinary Confederate fire and was repelled. Company G’s color bearer was killed during the retreat, so Beaty returned through 600 yards of enemy fire to recover the flag. The regiment had suffered severe casualties in the failed charge. Of Company G’s eight officers and 83 enlisted men who entered the fight, only 16 enlisted men, including Beaty, survived the attack unwounded. With all officers killed or incapacitated, Beaty took command of the company and led it on a second charge toward the rebel lines. The second attack successfully pushed the Confederates from their fortified positions.

Beaty’s Legacy

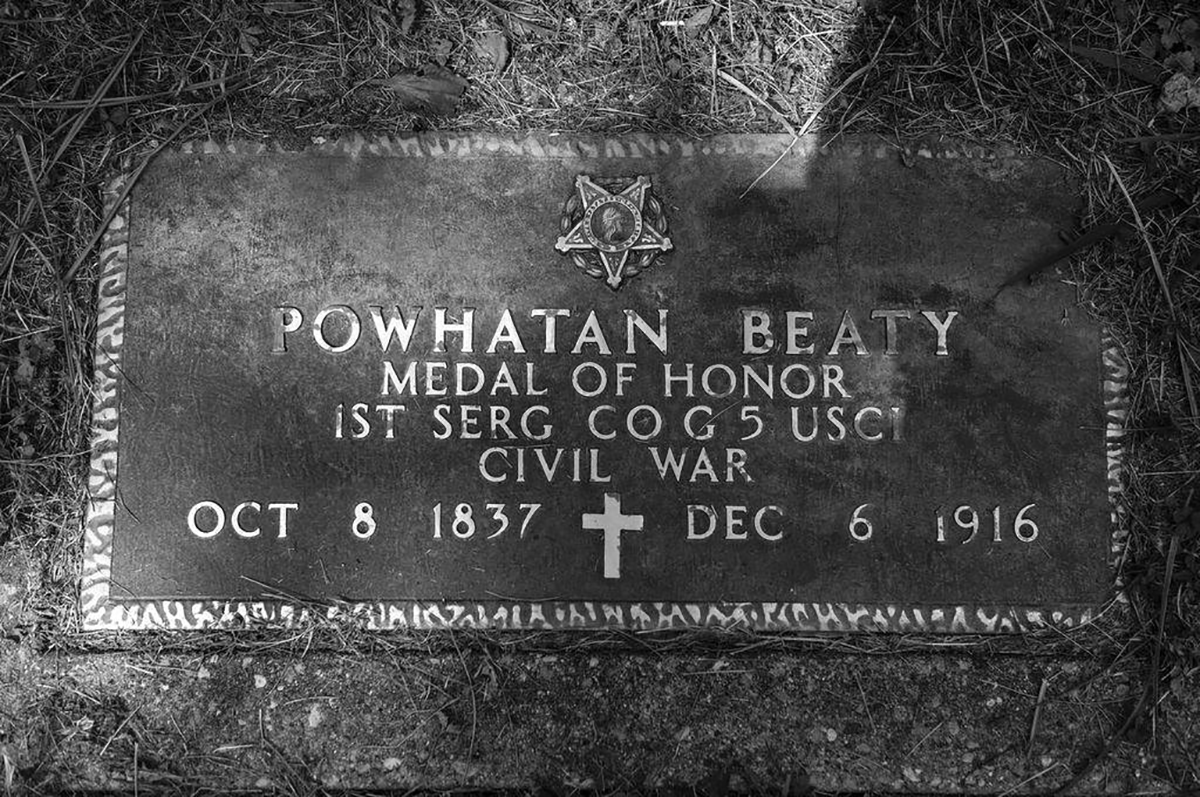

Gen. Benjamin Butler commended Beaty on the battlefield for his actions, and, seven months later, on April 6, 1865, Beaty was awarded the Medal of Honor.

Powhatan Beaty’s Medal of Honor citation: “Took command of his company, all the officers having been killed or wounded, and gallantly led it.”

Beaty continued to distinguish himself during the war. His heroics during the Battle of Fair Oaks in October 1864 earned him an acknowledgement in the general orders to the Army of the Potomac. Col. Giles Shurtleff, the regimental commander, twice recommended Beaty for a promotion to commissioned officer, yet nothing came of the requests.

“African-Americans weren’t allowed to receive commissions, so the only thing you could do was prove yourself,” Gibbs said. “They just hoped that somebody would recognize them for the achievements that they would make, and they fought as hard as they could. They were willing to give their lives.”

Beaty participated in 13 battles and many skirmishes by the time he left the Army.

As a tribute to Beaty’s significance in U.S. history, in 2000 Congress designated the Interstate 895 Bridge over Virginia Route 5 as the Powhatan Beaty Memorial Bridge. Beaty, along with many other prominent African-American figures, is buried in the Union Baptist Cemetery in Cincinnati.

In the wake of great American heroes like Powhatan Beaty, one can wonder what motivations today’s service members might have, as varied as they probably are.

“Times are different and different people have different goals,” Gibbs said. “But, there may be those who are inspired by Soldiers from the past. Then, democracy is something people want to protect, to protect what freedoms we have, so that doesn’t get changed or shifted.”

Perhaps, then, Powhatan Beaty’s fight for freedom might be looked at as a foundation for today’s democracy. Perhaps many of today’s service members are ready and there for their country because they want to protect the freedoms that Beaty fought for more than 150 years ago.

Sources

- Ohio History Connection

- Sgt. 1st Class Joshua Mann, Ohio Army National Guard historian

- “African American Recipients Of The Medal Of Honor,” by Charles W. Hanna

- “The Encyclopedia Of African American Military History,” by William Weir

- BLACKPAST website