Ohio National Guard News

Counterdrug Task Force mission is personal

|

|

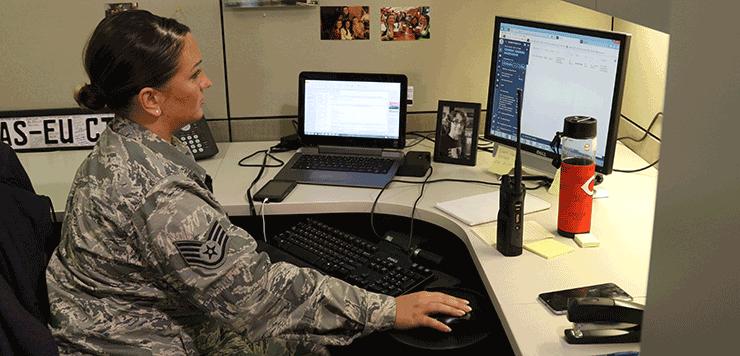

Staff Sgt. Alicia Stayonovich, a criminal analyst for the Ohio Counterdrug Task Force, tracks drug trafficking patterns as part of her work with Homeland Security Investigations, an arm of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, in Cincinnati. Stayonovich, who provides real-time intelligence and analysis for HSI agents in the field, takes a personal interest in helping remove drugs from the street as her brother died of a heroin overdose in 2015. |

|

Alicia Stayonovich with her brother, Travis Sparrow, in 2003. |

Alicia Stayonovich smiles for a photo with her brother, Travis Sparrow, in their parents’ home in Wapakoneta, Ohio. |

COLUMBUS, Ohio (04-25-18) —Two men in an unmarked black sports utility vehicle sat idle, engine off, in a parking garage. They had been there long enough that their coffee had cooled from near boiling to room temperature. Traffic was brisk, but they gave it only a cursory glance. They were staring through tinted windows, focused on a sedan one aisle over and at the occupants inside. A blast over the hand-held radio broke the monotony: “It’s them, we’ve got a match.” Across town in an unassuming office building, Staff Sgt. Alicia Stayonovich, a criminal analyst with the Ohio Counterdrug Task Force, put down her handset and sank back in her chair with a sigh. Her work with Homeland Security Investigations, the principal investigative arm of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, has always been rewarding but sometimes can be mentally exhausting. Stayonovich is not your usual federal employee or your typical Citizen-Airman. Rather, she is part of the Ohio National Guard’s Counterdrug Task Force, using her training to assist law enforcement at the local, state and federal levels to fight drug trafficking. In her day job, Stayonovich provides real-time intelligence and analysis for HSI agents in the field, identifying key information from observations to field reports, which enables agents to respond to events as they happen, with the best information available. In her traditional National Guard role, Stayonovich spends her drill weekends poring over maps and geospatial reports as an operations intelligence analyst with the 178th Wing out of Springfield, Ohio. “They are on the move.” The radio chirps as Stayonovich continues scanning through files critical to the operation. “Units are following.” Stayonovich’s role is to keep the information flowing. Her fingers fly over the keys of her computer, searching myriad law enforcement databases for red flags. Border crossings, prior arrests and lists of aliases all scroll down the screen. In a database of vehicles, one selection is highlighted. The vehicle is on a list of cars with a known “trap,” a hidden compartment, typically used to smuggle illegal substances or weapons. After passing the new information on the vehicle to the agents, Stayonvich’s eyes drift, as they so often do, to the picture directly next to her computer. The frame holds a photo of her brother, Travis, who died from a drug overdose in 2015. “I got the worst phone call you can ever imagine.” Stayonvich said. “It changed my whole entire world.” Travis had used drugs for most of his adult life; opioids were his drug of choice. His lifelong struggle with addiction is the driving force behind her desire to work in law enforcement. “When I was hired on to work with counterdrug, he was still with us and not using.” Stayonovich remembers. “When I interviewed, I was honest and told them. I said ‘It’s a passion of mine.” Six months after Stayonovich started with the CDTF, her brother had a relapse. Three days later, he was found in a local hotel room, dead from an overdose. “I woke up to my phone ringing. I ignored it, but it rang again. It was my dad. I called work, because obviously I wasn’t coming in that day.” Within two hours, a coworker from the CDTF was at her apartment with a bag of groceries and Lt. Col. Alexander Alston, the coordinator for the CDTF, was on the phone, telling her to take all the time she needed. At the funeral, members from both the 178th Wing and the CDTF were there, not just for Stayonovich, but also for her family. Airmen from the 178th also raised money to help pay for funeral expenses. Stayonovich wants people to remember her brother for the person she knew, a good man. “He had a great heart; everyone loved him,” Stayonovich expressed. While a 10-year age gap separated the siblings, they were extremely close. “He was so proud of my service. At his funeral, everyone came up and told me how proud he was.” Travis’ descent into addiction was a tumultuous trip. What started out as simply hanging out with the wrong crowd turned into smoking marijuana. From there it took just one weak moment and Travis started a two-decade battle with opioid addiction and depression. After a run in with the law, Travis cycled through incarceration, to job loss, to depression, to using. Travis tried several rehabilitation programs, but due to circumstances caused by his incarceration, meeting the program policies was a challenge and he was eventually removed from the program. After his death, his family found journals stretching back more than 20 years, the day-to-day thoughts of a brother, son and father — vivid views that ventured from Travis’ desire to get clean to his struggle with addiction and all the thoughts in between. “What on Earth would possess a person to continue using any drug after that first throwing up experience most people have on heroin!,” Travis wrote. “Who’s honestly willing to throw their whole life away assuming you don’t wind up dead? It’s a pretty sad existence.” He wrote of the pain he knew he was causing his family and how he hated himself for his weaknesses, but that he wanted to be regain their trust and that of his community. “One of the biggest things I would like to see, is for people to realize not all addicts are low-lives.” Stayonovich said. “It’s a constant battle, if we don’t get them the resources to quit, they aren’t going to change. There is no typical addict.” The chirp of the radio breaks Stayonovich’s train of thought. “We got it, looks good.” Found in the vehicle was almost a half million dollars of cocaine, a sizable bust. “That’s all I want, is for it to not be available for people to use. I don’t want what happened to me and my family to happen to anyone else,” Stayonovich said. “I want to be a part of the fight against addiction and getting drugs off the street.” In 2017, the CDTF supported law enforcement operations that resulted in more than 14,000 pounds of drugs seized, valued at more than $50 million dollars. Stayonovich knows that it isn’t the end of the drug war, but it’s a victory and progress. Travis would be proud. For more information on the Opioid Crisis and ways you can be a part of the solution, visit the following websites |

|