Celebrating Native American Heritage Month

A Beloved Man: Guard member with Cherokee heritage leads with character, values, beliefs

Story by Sgt. 1st Class Chad Menegay, Ohio National Guard Public Affairs

COLUMBUS, Ohio (11/26/19)

Ani-Yvwiya, a Cherokee word for the name of their tribe, translates as the Real People.

This might be read as: genuine, authentic, true. Real People.

Cherokee people live across the United States, but they are mostly concentrated in Oklahoma and North Carolina.

One of the 819,000 Real People living in the U.S. is Ohio Army National Guard Capt. Chris Brandt, who works full time as an administrative officer for the Ohio National Guard’s Directorate of Installation and Resources Management, and in his traditional Guard role as an executive officer for the 216th Engineer Battalion, headquartered in Cincinnati.

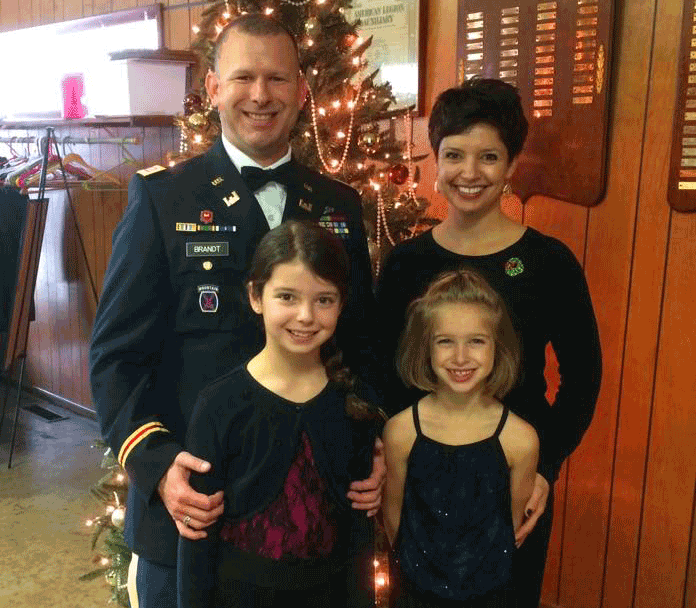

Brandt is a regular American family man, a husband to his wife, Jen, and a father of two daughters: Katy, 15, and Riley, 12. The Brandts, who live in Kettering, Ohio, care for a black Labrador Retriever, Sapper, 10.

Now there was no one alive but the man and his family.

~ from “Myths of the Cherokee” by James Mooney

Family seems to be the most important thing in Chris’s life.

“I joined the National Guard because I felt a strong desire to serve my country again, to help create a safer world for my wife and daughters,” Chris said.

He first served in the Navy as an active-duty machinist’s mate, which Chris described as a “jack-of-all-trades” role in the Navy’s engineering community. He did a lot of combat search and rescue in that enlistment, he said, and served in Operation Desert Storm/Desert Shield and Operation Restore Hope (Somalia). After a 15-year break in service that included marriage, children, earning two bachelor’s degrees (communication and psychology), a master’s of education in sports and exercise, and work as a high school teacher, Chris felt the need to return.

“He sets a very positive example of what it means to be American for our daughters,” said Jen Brandt, who comes from a long line of military members in her family. “Chris sets a very positive example of what it looks like to serve for our daughters.”

Chris, like many other military service members, is called on to travel often. Still, he finds time to be a devoted family man.

“When Chris is home, he is present,” Jen said. “He is very present in our lives.”

There is much to attend to.

Katy is heavily involved in her dance school, and Riley plays basketball. The two girls were also recently nominated by their peers to serve as suicide interventionists under the program Hope Squad.

“That was a pretty awesome thing to find out that Katy and Riley’s peers think that they’re people who they would feel comfortable going to, to talk about some pretty heavy-duty stuff,” Chris said.

He was reluctant to take credit for his daughters being elected for a leadership position; instead he shined light on his wife, who is the assistant director of fitness at the University of Dayton and supervises over a hundred employees.

“I think they see probably most significantly in their mom, a strong, decisive, positive leadership role model,” Chris said. “If I have anything to do with it, it’s just because they see those same leadership qualities in my job and the amount of work that you put into making good, ethical, morally-correct decisions and understanding the impact of them.”

Chris cites his character, values and beliefs as heavily impacted by his Cherokee culture.

The Cherokee priest still treasures the legends and repeats the mystic rituals handed down from his ancestors.

~ from “Myths of the Cherokee” by James Mooney

“My version of a worldview, if you will, is influenced by what’s important in the Cherokee culture,” Chris said. “Take care of the earth. Act honorably. Be honest. Try to have fun. There are a lot of misunderstandings about what it is to be Indian, you know, Cherokees aren’t a stoic people. A sense of humor is highly valued.”

Chris, who grew up in Texas, has strong family roots in Oklahoma, where both sides of his family are from, and, in particular, he still has relatives in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, the capital of the two federally recognized Cherokee tribes based in Oklahoma.

Chris is a member of Cherokee Nation which has more than 300,000 tribal members, making it the largest of the 567 federally recognized tribes in the United States.

The Cherokee Nation is the sovereign government of the Cherokee people, which gives Chris dual citizenship.

He can trace his lineage back to one of the great Cherokee figures in history, Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation John Ross (1790-1866), Chris’s great-great-great-grandfather.

Ross, who fought under Gen. Andrew Jackson at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend against the British-allied Upper Creek warriors during the War of 1812, was eventually forced to shepherd his people in their removal to the Oklahoma Territory after Jackson’s signing of the 1830 Indian Removal Act.

Ross is celebrated for devoting his life to resisting U.S. seizure of Cherokee lands in Georgia. He made allies in Washington D.C., directly petitioned Congress for the Cherokee cause and even sued in the U.S. Supreme Court and won.

In the end, the Supreme Court decision was ignored and troops forced the Cherokee into stockades at bayonet point while their homes and belongings were looted. Then, they marched the Cherokee more than 1,200 miles to Indian Territory. Whooping cough, typhus, dysentery, cholera and starvation were epidemic along the way, and historians estimate that more than 5,000 Cherokee died as a result of the journey, including Ross’s wife, Quatie.

Ross is credited with helping rebuild their community and government in Oklahoma.

Chris, of course, is proud of his lineage to Ross, but he seems more concerned with modern Cherokee issues than in revisiting injustices of the past.

“I don’t speak for all indigenous peoples, but my opinion is I can’t hold Andrew Jackson and his broken promises against the American people today,” Chris said.

It is unrealistic to think that the Cherokee could sue and win all of the Cherokee homeland back, he said.

“What we can do,” Chris said, “is continue to live within the guidelines of our culture. We can continue to celebrate who we are, and we can continue to fight to be recognized as a living, breathing people today, not something that no longer exists.”

Then the mother recognized her two sons, and said, “Let us go back and dance for the dead come to life.”

~ from “Myths of the Cherokee” by James Mooney

Chris believes that it’s important for Cherokee and other Native American tribes to be recognized as real members of U.S. society.

“This observation (American Indian and Alaska Native Heritage Month) is important to me because there is a gap between modern America and the American indigenous communities,” Chris said. His master’s project was on the misappropriation of American Indian culture as sports mascots.

“No other real, and that’s the important word, real group of people are used as mascots,” Chris said. “You kind of dehumanize people when you do that. We don’t really as a people exist until, you know, November. Most of America sees American Indians as a homogenous group, you know, Sioux should be able to speak to Cherokee, and you should be able to speak to Navajo, and it’s all the same language, whereas that’s not the case. At the time of colonization, there were approximately a thousand different American Indian nations.”

He wishes Americans in general were more aware of issues American Indians face today, issues like teen pregnancy, alcoholism, drugs, short lifespan, poverty and reservation conditions.

“Really, in modern America, the only place that American Indians do exist are in sports mascots, movies and history books,” Chris said.

He does his best to ensure that his daughters are socially and culturally aware.

“I don’t want the Cherokee Nation to die because my generation didn’t do our duty to pass on the culture, just like I don’t want my daughters to not understand that, you know, the Ross family was Cherokee and Scot,” Chris said.

Chris celebrates his entire heritage with his daughters, which includes Scottish and Danish roots. It’s as important to travel to Scotland and visit the Province of Ross as it is to visit the Smoky Mountains, he said.

“When the girls were young, I’d read them Cherokee stories,” Chris said. “I’d read them nursery rhymes and all that kind of stuff, but they also heard about Grandmother Spider and how the earth was created.”

One such book, “Myths of the Cherokee,” by anthropologist James Mooney (1861-1921) is a volume comprising 126 Cherokee myths, including sacred stories, animal myths, local legends, wonder stories and historical traditions. In North Carolina, Mooney lived for several years with the Cherokee, studying their language, culture and mythology.

Chris has a number of Cherokee items in his home, including bracelets, a flute, a bone choker and a Cherokee Nation flag.

“One of the things I don’t have that I really would like to get or at least get the patterns, so I could make it myself, would be a traditional ribbon shirt,” Chris said. “Traditional Cherokees wore the low moccasins, deerskin breeches, a breech cloth, a distinctly Cherokee turban and a ribbon shirt, which was a patterned shirt with ribbons integrated into the pattern used for ceremonies or social gatherings.”

Chris is a hunter who eats what he hunts.

“I was taught by some cousins on how to make traditional bows,” he said. “I enjoy being out in the woods, and I think some of that is because that’s the way my ancestors were.”

He plants heritage seeds, so that his family can enjoy Cherokee corn and peas. Jen says that she married him because he is such a wonderful cook.

“A lot of the stuff people would consider kind of low country cooking,” Chris said. “It’s how I was raised, making your own biscuits, those things that are identifiable Cherokee and those things that are just Joe Farmer type stuff, cast-iron skillets and stuff like that.”

Some old people say that the moon is a ball which was thrown up against the sky in a game a long time ago.

~ from “Myths of the Cherokee” by James Mooney

Chris has played Cherokee stickball, similar to the historic game of lacrosse. Stickball began in prehistoric times as a way for tribes to settle disputes without going to war.

“It’s pretty brutal,” Chris said. “They had ambulances standing by, and those medics were pretty busy. I was just trying to not get too many broken bones in the process.”

Cherokee are said to have once considered warfare a polluting activity. After warfare, the warriors once required purification by the priestly class before participants could reintegrate into normal village life.

Certainly, they have a reputation as a brave people and have fought both alongside and served in the U.S. military in every war, minus understandably siding with the Confederacy in the Civil War.

American Indians altogether serve in their country’s armed forces in greater numbers per capita than any other ethnic group, and they have served with distinction in every major conflict for over 200 years.

“Some of that is culturally-based,” Chris said, “with the importance of being a warrior in the culture. If you’re indoctrinated in the culture, you’re drawn toward that, and in other cases it’s a way to get off the reservation. There are not jobs. Reservations are not necessarily in the best parts of the country.”

As for Chris himself, his military heritage is strong, with relatives having served in the Navy, Air Force, Army and Marines.

“The camaraderie between service members, even across generations, it drives home that I am a part of something much bigger than myself,” Chris said. “The things we do, impacts people, even when they are uninformed of what we are doing for them.”

One of the major roles that Chris assumes as an engineer officer is to mentor Soldiers.

“There’s a big piece in the Cherokee culture where you show respect to your elders, you seek guidance from them,” Chris said. “I see a lot of parallels between the Cherokee culture and the military culture in that sense.”

One person who Chris has worked closely with as an engineer officer is Sgt. 1st Class Lee Degaugh, currently the operations noncommissioned officer in charge for the Ohio Army National Guard Command Group.

“As a platoon leader, he was very effective,” Degaugh said. “His platoon was always scoring high on evaluations, situational training exercise lanes, stuff like that, because he listens to his noncommissioned officers. His troops respected him, and everybody liked him. He was very friendly and actually took the time to get to know his Soldiers.”

Training combat engineers to support front-line infantry in a time of war is one thing Chris cites as work that may, in ways, create a safer world for his wife and daughters.

“Our neighbors see the sacrifices our family makes,” Jen said. “They thank him, and their kids see what it’s like to have a Soldier in their community. He’s a living, breathing example of what it looks like to be in the military.”