In Their Own Words:

75th Anniversary of D-Day

Compiled by Sgt. 1st Class Joshua Mann, Ohio Army National Guard Historian

(06/06/19)

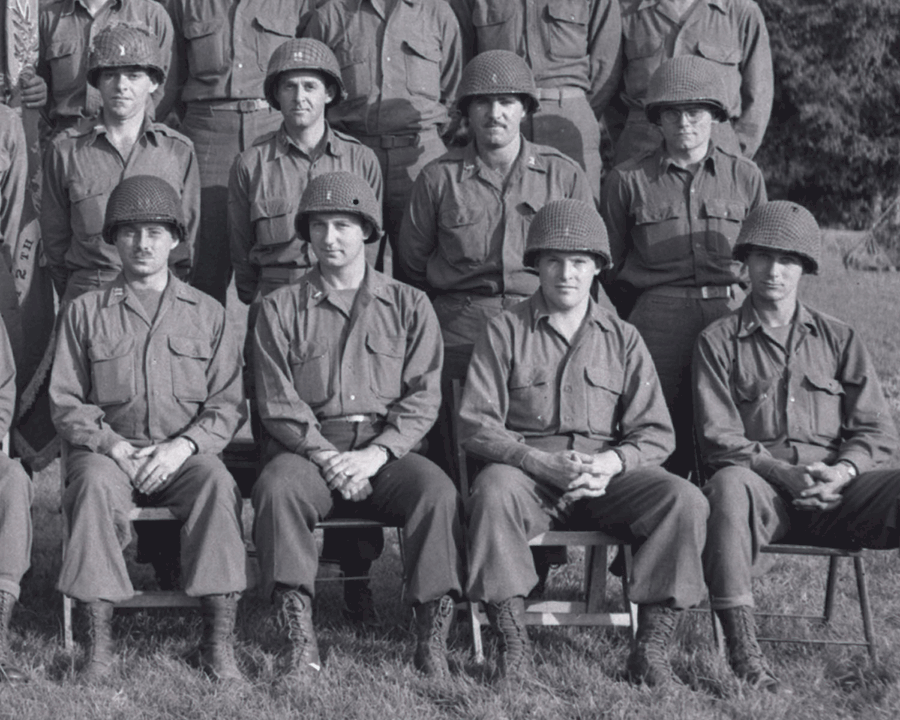

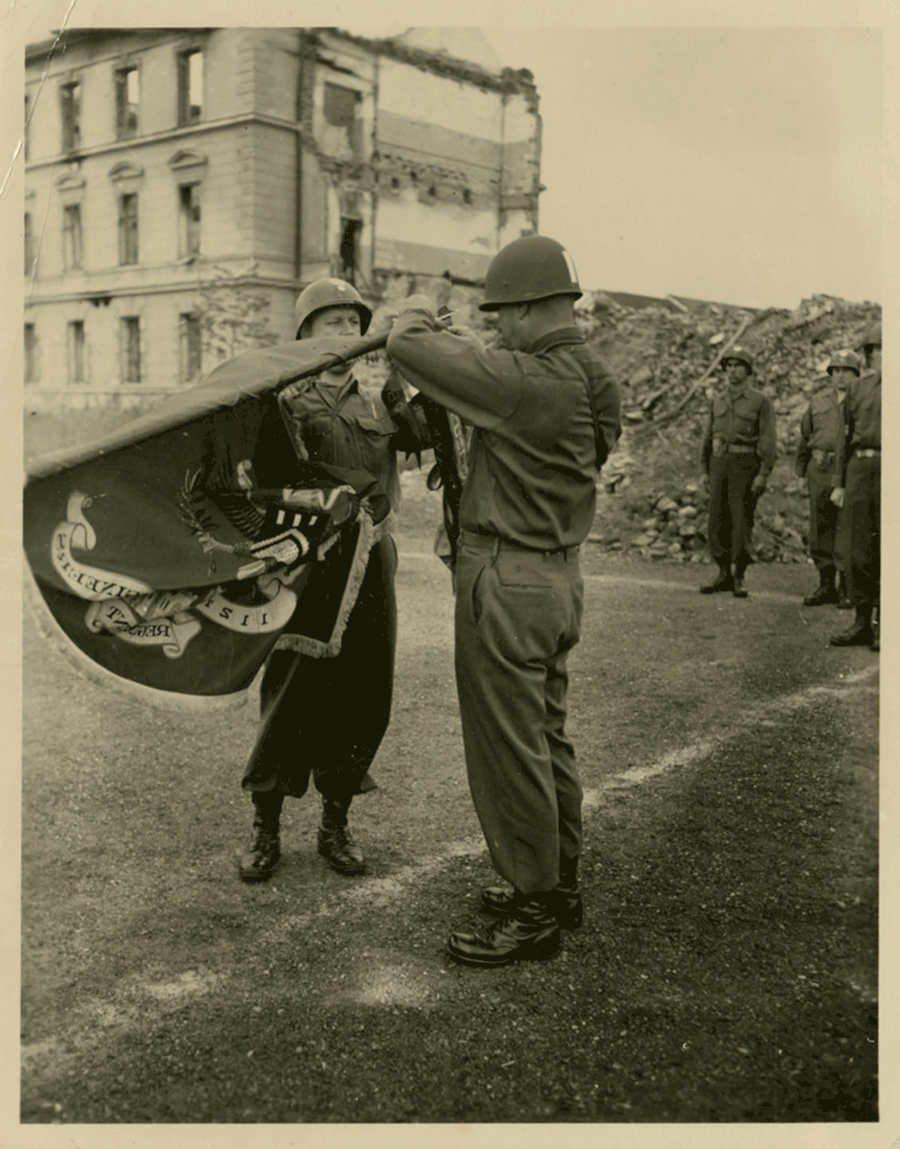

On June 6, 1944, more than 160,000 Allied troops landed along a 50-mile stretch of beaches at Normandy, France. Two Ohio National Guard units, the 112th Combat Engineer Battalion and 987th Field Artillery Battalion, were involved in the D-Day invasion. The 112th would land at Omaha Beach in support of the 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions, where it would receive the Presidential Unit Citation. The 987th, with its M12 155 mm gun motor carriage, was prevented from landing as scheduled on June 6 and hit the beach on the morning on June 7 at Gold Beach, in support of the British 50th Division.

The following accounts are from Soldiers of the 112th Combat Engineer Battalion, which was based in the Cleveland area. Written in their golden years, these accounts offer a first person account of the historic events 75 years ago.

1st Lt. Clinton S. Learn, Battalion Adjutant:

After dawn on the morning of June 6, 1944, vessels and landing crafts of all descriptions could be seen on all sides sliding onward cutting through the choppy waves. It was D-Day and H-Hour 0700 was nearing as we approached the English Channel and coast of France. Finally the cliffs and hills could be discerned. Our planes droned overhead, the Navy’s large guns boomed and everyone was very tense. New and peculiar noises began to register nearer and louder.

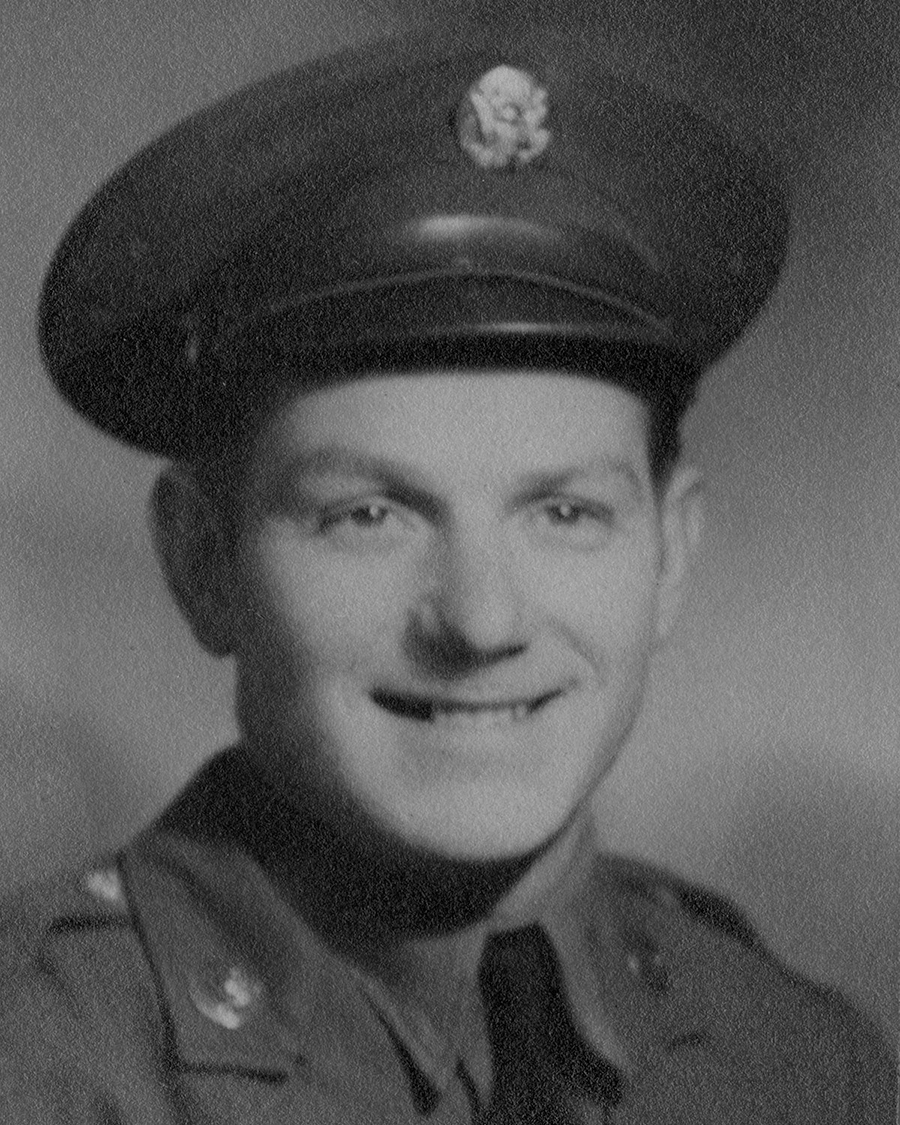

Sgt. Alfred Rasche, Company B:

I guess I did sleep a little but I awoke when the big doors of our ship were opened and the ramp was let down onto a large raft which was called a “Rhino.” Our heavy equipment was being loaded — compressors, Diamond-T trucks, the bulldozers, and other trucks. Most of these were loaded with TNT, plus every man was carrying something in addition to his regular gear… a pack of TNT, a mine detector or a bangalore torpedo — so you see we were all very explosive.

Capt. Grandison K. Bienvenu, Commander, Company B:

When we boarded the landing craft, we were loaded down with equipment. We had a field pack for the men. The officers wore a musette bag. I had binoculars, map case, carbine, trench knife, compass, canteen. I had a chest-type gas mask, rubberized, and was to act as a life preserver in the event that one was needed. However, if any of us needed a life preserver, it wouldn’t have been big enough. With all the equipment we carried, we’d have sunk straight to the bottom. The men all carried at least 25 pounds of TNT, including the officers. So we were pretty well loaded down.

First Sgt. Rans Blando, Company B:

I watched the war ships and rocket launchers send their gifts to Hitler and trained the glasses ashore and saw them strike. Water was rough. Everyone was in a good mood and immediately shut up as two bodies floated by us. We then made an agreement that we would meet in Cleveland every June 6.

Bienvenu: As we approached the beach, it was all in daylight at that time, and as I remember, we were scheduled to go in at H +120 minutes, which was the sixth wave, but we were probably the second wave that actually landed as a wave, as others were wiped out as they approached. As we were going in, we could see all these sunken boats and vehicles that had run off the boats, just the top showing. Everybody going in different directions, and shells landing, planes flying overhead. The confusion was just terrible with all the equipment and men piled up along the beaches.

Learn: Enemy bullets ricocheted off the upper structure of our ship. Approaching shore we hit a sand bar and the skipper had to back off to try another lane. Moving a bit farther ashore, the ramps were dropped but the water was still too deep for safe discharge. Further maneuvering was done. The water was deep and the waves lifted us off our feet as we staggered and struggled onward amid enemy shooting. Some crafts had to unload in deep water. We worked our way up the beach through obstacles, assisting our casualties keeping ahead of the tide.

Rasche: When our Rhino grounded, we all jumped into waist deep water. There seemed to be a lull in the firing for a few minutes. We ran to the first depression and took the little cover that was afforded. At this time, we came under fire again, by what I could not tell except that it was very rapid fire. We then ran to the high water embankment where many GIs were taking shelter, both dead and alive.

Blando: The ramp went down and we were waist deep in water. We walked ashore. No shelling at that time. Just the zip zip of small arms fire going by. Lots of smoke. Pappy Glen Kloth, at the edge of the water, asked me to cut his life preserver loose and I started to do so when an 88 shell came over and exploded a hundred yards away into the sea. I found myself standing there with my knife in my hand and Kloth was gone as were all others.

Bienvenu: We were wet and scared, hungry, insecure, didn’t know where anything was. You’d look around you and you could see people being killed. And equipment blown up, ships being sunk. That’s all kind of vague, the panorama there is just hard to describe.

Blando: It did not take much encouragement for me to start my run for the safety of the vertical dirt at the base of the bluff. The shells and small arms fire was now increased. I would run like hell and flop down awhile and up and run again.

Rasche: At this time I received the signal to move up. I passed it on. After about 200 yards, I looked back to see if all my squad was coming when a shell burst hit where we had just been — so much for luck! As we were going up the hill, we were in sort of a gully. When we got to the top of the hill, we came into an open area with very little cover. We were in staggered formation and, lo and behold, along came one old Frenchman who stopped by each GI and saluted. We never did find out if he had too much to drink or was just thankful to be alive.

Blando: Word came to me that we were all to move to the north and exit the beach. I was informed to bring up the rear and to be assured that all B Co got off the beach. That turned into a chore. Most of the men started to move to the north and we did fine till we reached the exit. Shells started to come over and several of our men jumped off to the left into a German mine field. I had to yank them out of there and kick butts and threaten some to get them moving. I warned them that they would not have to worry about a shell, they better worry about me cause I was ready to leave that hot beach and they were not going to take up too much of my time. Some of those poor bastards got to me I guess. Hell, we were all afraid, so what was new.

Learn: Our acting battalion commander, Major William A. Richards, was killed early on D-Day adding to the horror and confusion we suffered. Under determined enemy resistance our troops opened a roadway off Omaha Beach around the cliffs inland in vicinity of Saint Laurant-Sur-Mer, France by nightfall.

Rasche: I was able to locate our company in another field. When we got there, the Captain told me to take my squad and go back to the beach and try to find some workable mine detectors, which wasn’t hard to do because the beach was full of castoff army equipment. There was no firing on the beach now and one could stand up and look around. The tide was in and wrecked assault boats were everywhere — loaded boats trying to get in, others trying to get out. Bodies of the dead were in this bobbing mess. Even today I’m thankful that I had the opportunity to return to the beach that day after — one does not realize how little one can see when you have to keep your head down. Today one could see all around and what I saw is still in my mind as I saw it that day.