112th Engineer Battalion staff connects to their past

Story by Sgt. 1st Class Joshua Mann, Ohio Army National Guard Historian

CLEVELAND, Ohio (09/09/19)

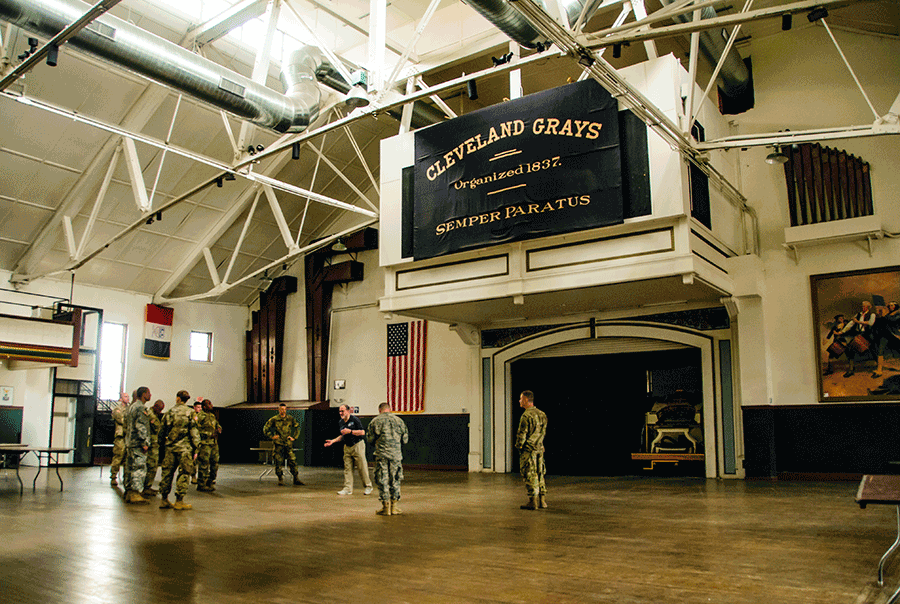

In the summer of 1837, a brief Canadian rebellion against Britain brought the possibility of war uncomfortably close to the young city of Cleveland. On Sept. 18, 1837, in response to a perceived threat along the Lake Erie shore, 78 men signed their names to the rolls of the newly formed Cleveland City Guard. Less than a year later, the City Guard voted to change their name to the Cleveland Grays, a nod to the color of their distinctive uniforms.

One hundred and eighty-two summers later in downtown Cleveland, a man hawks peanuts and water to passers-by, who are making the short walk from their parking spot to Progressive Field to catch a Cleveland Indians doubleheader. Just a few feet away, a group of Soldiers, in green camouflage uniforms, assemble on the steps of a massive stone building for a photo. As the Soldiers stand erect, the foot traffic briefly pauses as the photographer snaps the photo. These are not the first Soldiers to be photographed on these steps. For a brief moment, history collides.

“I’ve never been here before.” said Maj. Eric Holtzapple, commander of the 112th Engineer Battalion. Just a few hours prior, he and his staff were conducting annual training about an hour away at Camp James A. Garfield, located near Newton Falls, Ohio. Inside the stone walls of the Grays Armory, which opened in 1893, he and his staff immerse themselves in their heritage. Ohio’s oldest unit, the 112th Engineer Battalion perpetuates the lineage of the Cleveland Grays.

“This goes back to the 10 years I spent in the battalion, both as enlisted and officer, before I was aware of our history.” Holtzapple said. “Walking in and seeing the 112th colors from World War II on the wall reminded me about this history and how it ties the Grays to the 112th.”

The Grays were one of the first Ohio militia units to volunteer for the Civil War. During the War with Spain, the Grays helped organize a hybrid infantry and engineer regiment. However, the war ended before they could leave the United States. After the war, the engineers reorganized in the Ohio National Guard and fought in France and Belgium in World War I, landed on Normandy on Omaha Beach in World War II and more recently deployed to Afghanistan in support of the War on Terrorism.

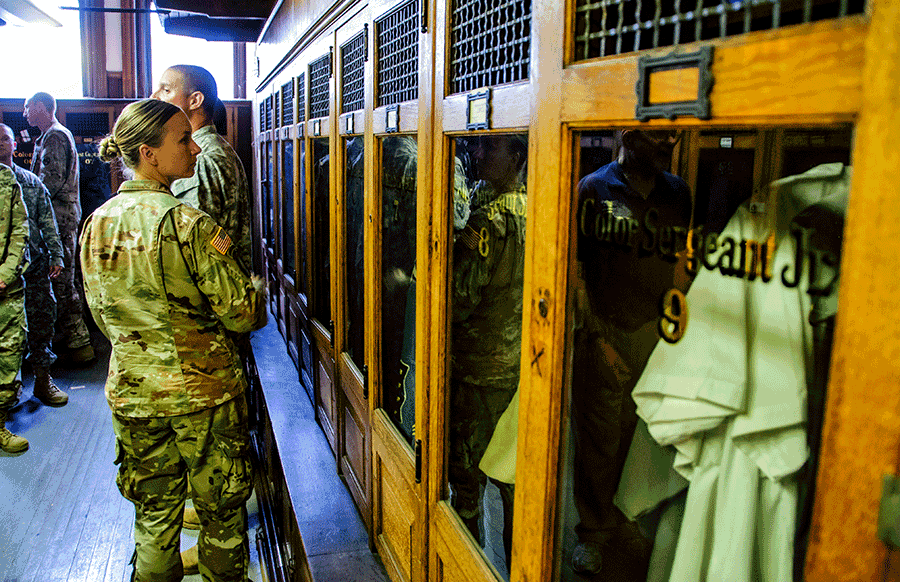

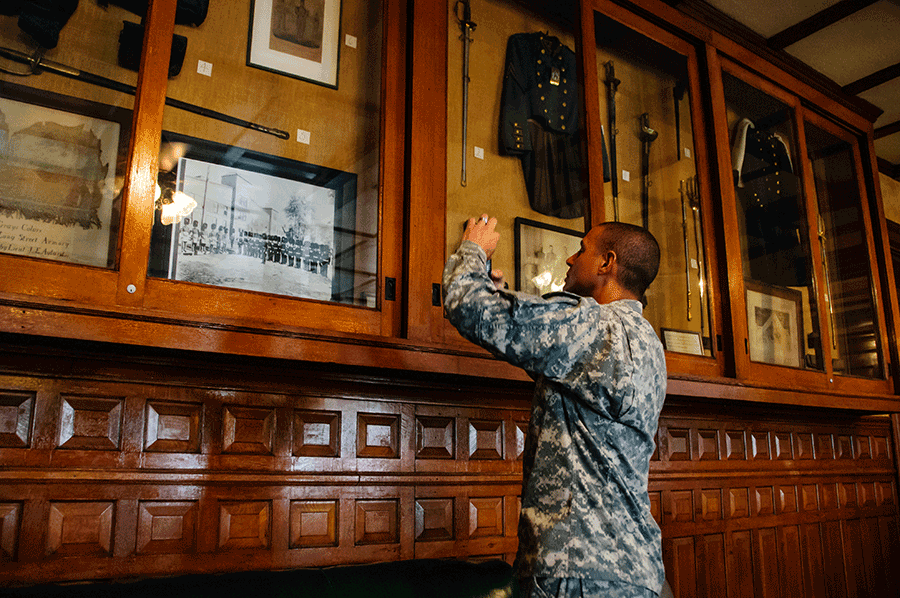

Herk Rauzi, the chairman of the museum committee for the Grays, led the staff on a tour of the armory, explaining in detail the building and various artifacts on display — the confederate cannon captured at the battle of Corricks Ford, Virginia in 1861 that commands the lobby; the French automatic rifle brought home from World War I; the ornate wooden newel posts with hand carved “CG” monograms at the landing of the stairs; the grand ballroom that held lavish and elaborate military balls — all symbols of the military and social balance of a 19th century independent militia company.

For 1st Lt. Valerie Stearns, the battalion training officer, seeing the material culture up close helped her learn how the organization evolved from a militia company to today. “Looking at the artifacts and imagining the individuals being there at that moment in time was important. I’m excited to represent and celebrate that heritage as a member of the 112th,” she said.

Added Holtzapple: “We stand on these Soldiers’ shoulders. From the Grays, to the 75th anniversary of D-Day (which was marked earlier this year), this is the spark that keeps history going in this battalion.”